We are all drowning in information, and that makes it very difficult to pick apart what is truly important vs. what is merely interesting.

If a leader’s first job is to see the world as it truly is, then we should be thoughtful about the type, volume, and source of the information that we are consuming. Whether we’re conscious of it or not, the information we absorb will shape the way we see the world, and if we’re not careful, it can lead us astray.

Information can tell us almost anything we want. It doesn’t take much for us to find (or be fed) information that confirms something that we want to see, or denies something that we don’t.

What we really need is intelligence.

Intelligence is something that helps us to make timely decisions and take appropriate action. We can do that because intelligence isn’t just the raw inputs of information, it is the output of a deliberate process of analysis and corroboration. Without intelligence, we can easily fall prey to the biases, quick conclusions, and poor decisions that result from examining information in a vacuum. As with so many of our leadership lessons, we learned this the hard way during our time in Special Operations.

One night in Afghanistan my section and I were out on a patrol when an ISR plane came on station high in the sky above us to relay critical information. ISR stands for Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance - critical assets to any combat leader on the battlefield and any business leader in the boardroom.

As the mission went on, our eye in the sky notified us of some heat signatures on the ground in our immediate area, putting us on high alert. This was less than 2 years after Operation Anaconda went down, so the advent of cave and hidey hole warfare was a clear and present possibility. By this time we had already seen plenty of little nooks and crannies and enough rockets, mortars, RPG’s, and roadside bombs to take any report seriously.

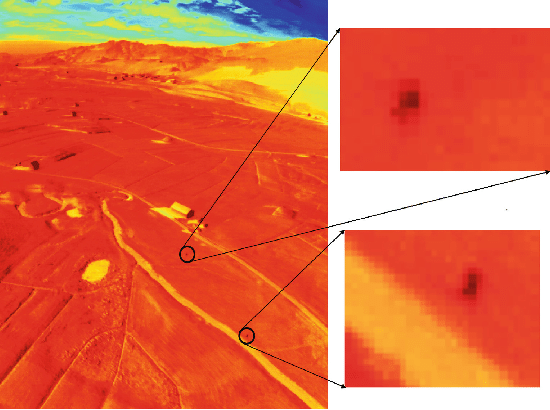

“A sample image recorded from the FLIR thermal camera at an approximate altitude of 70 m. Two humans are pointed out.” Credit: Researchgate.

With our Air Force Tactical Air Controller, Charlie, on the mic with the aircraft, and me in relay with my team on the ground and my higher command, we began the process of gathering intelligence to form a clear picture. Clarity comes from gaining a picture of the whole truth, a common operating picture that combines what everyone is seeing from their unique vantage points. We were close enough to the heat signature on the ground for it to matter, but too far to know why. We needed to confirm or deny a threat.

Splitting my section into support (stationary) and maneuver (close up) teams was required to get the ground truth of the matter. This is where things get complex quickly. Splitting your element when there is an unknown, potential enemy position on the battlefield can be catastrophic if something goes wrong. And the potential for something to go wrong can happen to any team on the battlefield, regardless of how well you operate.

We began to close in on the mysterious heat signature while radio communications evolved between various elements: the ISR plane above, our command at the fire base, my support element around me, and our maneuver team on the move. We were ready for a fight. We just needed to fix the location of our enemy. And I needed to hold tension between all elements in the process to gain the intelligence necessary to act.

In moments like this, everyone wants to know what’s going on. Immediately.

My chest tightened, maintaining a cool voice while working with Charlie speaking to a bird 30,000 feet above, me speaking to command 30 kilometers away, our maneuver team 300 meters away, and my support team spread across 30 meters in overwatch. Everyone wants more information from their position, everyone needs good intelligence to do their jobs. Everyone needs to trust each other in the process.

From the sky, the two heat signatures (ours and the mystery spot) look like semi-distinctive reddish blobs separated by three finger lengths of cool black space on a screen. From the ground, that black space looks like 600 meters of sharp, mountainous terrain with shale covered climbs and brush filled descents. From the command hooch back at the firebase, leaders listen intently and piece together the picture from the quality of our descriptions and their collection of maps and satellite photos.

From behind our sights, it all looks like opportunity, all we need is confirmation of the enemy to act. Imaginations run wild in moments like these…have we stumbled upon the next Tora Bora? Have we found the bastards that shot an MH-53 out of the sky just a week prior? Have we come upon an Al-Qaeda OP (observation post)? Perhaps we’ve fixed the position of rocket man, or a roadside bomber?

A Co. 2/75 Ranger Regiment Training in Yakima Firing Center, WA. Photo Credit: Army Times.

We wait. The maneuver element sends short and strained radio reports. The boys are working hard. The terrain is brutal.

Closing the distance between information and intelligence costs our maneuver team more and takes much longer than our comrades waiting eagerly 30km or 30k’ away want it to take. It costs effort. And it takes time, pain, and toil. Men in peak physical condition must push their limits to pay the price of gathering intelligence.

We lose sight of the maneuver team over the hill; every minute that goes by adds a pound of anxiety on our chests. Charlie and I buy us some time over the radios as the aircraft and command post grow more impatient by the moment. Everybody wants to kill the enemy. In moments like these, it feels like the entire task force is listening. Eagerly pressing you to do something. Anxiously pushing you to act now on the information at hand before we lose the chance.

When we are leading teams doing things that matter in the world, the stakes are always high. As leaders, we must always remember that information comes quick and easy, but intelligence takes time and effort.

We wait. Trusting in the effort and hopeful of the outcome.

Finally, “Dry hole!” is announced across the radio from the maneuver team.

“Roger. Dry hole,” I reply. An audible sigh comes in unison from our support position. I can practically hear the boys’ rolling their eyes and I hope they cannot hear me rolling mine.

“Clover leaf the position and confirm,” I continue. “Charlie, let the bird know we got nothing.” I report back to command and wait as our team conducts a detailed investigation.

The voice of the maneuver leader, Justin, remains calm, though his body is undoubtedly drenched in sweat and his heart rate is spiked.

The next few minutes are highlighted by tense exchanges between us and the bird, while I talk to command. Everyone who has information advocates from their perspective.

Convinced that they see something we do not, the crew in the bird is insistent. Charlie is patient, the boys and I are irritated.

“There’s nothing here,” Justin reports.

“Copy. Are you certain?”

“Yes. Over.” I trust this man with my life. I always have. And I trust his eyes - what he sees on the ground.

“Copy. Come on back. Over.”

We do a final report to the bird.

The detour has cost us time, but the effort is worth the intelligence gained to guide our actions. Charlie is trying to wave off the insistent bird, which proves to be more difficult than expected. My irritation turns to sarcasm as I invite the ISR crew to grab a parachute and come take a look for themselves if they like. They decline the invitation and fly on.

Another night chasing ghosts in the mountains continues.

Photo Credit: @danielcgold via Unsplash.

Some nights end up differently, most nights do not. This night left a lasting impression on me because I was the man on the mic. I was the leader in charge, responsible for everything that happened on the ground. And I was responsible for acting upon the information presented to me from the ISR bird, the command, and my Rangers. As leaders, we are often pulled in many different directions and we are often confronted with conflicting information.

We must take the time and effort to make sense of the details to form a clear, actionable picture.

A leader’s first job is to see the world as it truly is, not as we want it to be. In order to see the world as it is, we must take the information available and deal with it appropriately in order to uncover actionable intelligence to operate from. Because we as leaders need more intelligence, not more information.

Here are a few thoughts to consider when trying to gather intelligence from information:

Facts vs. Fables: Our emotions can cloud our minds and lead to negative or false interpretations. Negative interpretations lead to flawed judgment and actions that may lead to ineffectiveness. We may imagine the mongol horde in front of us, but it may be a field mouse.

Calm yourself and let the situation develop before acting upon your imagination.

Corroboration vs. Contradiction: If we want information to become actionable intelligence, we have to evaluate the data at hand, confirm (or deny) its significance, and formulate a wise approach. It is very plausible that upon your investigation, the information at hand will contradict the information initially presented. This doesn’t mean there are two versions of the truth, just two perspectives and the information might not be relevant to your needs.

Interrogate the information at hand and seek to corroborate its significance before you take action.

Interesting vs. Important: Lots of pieces of information are interesting, but not a lot is important when you have a job to do. Take in all that you can and filter out what doesn’t lead to increased effectiveness.

If you can apply it to your mission and it helps your team be more effective it’s important, otherwise it’s interesting and can become a distraction. If it’s a dry hole, leave it behind and move on.

Cover Photo: @pawelj via Unsplash.